Brazil favela chefs say poor should eat well, too

Source: AFP

PAY ATTENTION: Celebrate South African innovators, leaders and trailblazers with us! Click to check out Women of Wonder 2022 by Briefly News!

Brazilian chef Ana Lucia Costa is putting the finishing touches on an exquisite dish of marinated pork loin with lime and ginger, preparing to serve around 100 diners.

But this is no upscale Rio de Janeiro restaurant. She is cooking in her small shack in Rocinha, Rio's biggest favela, for people who would probably go hungry without her.

Costa runs one of 52 "solidarity kitchens" launched in Brazil by Gastromotiva, a charitable organization that provides volunteers in poor communities with culinary training, ingredients and a mission: not just feed the hungry, but delight their palates and bring some happiness to those who need it most.

"Why shouldn't poor people eat well?" asks Costa, who pours pasta and a tomato sauce seasoned with za'atar spice into the pan.

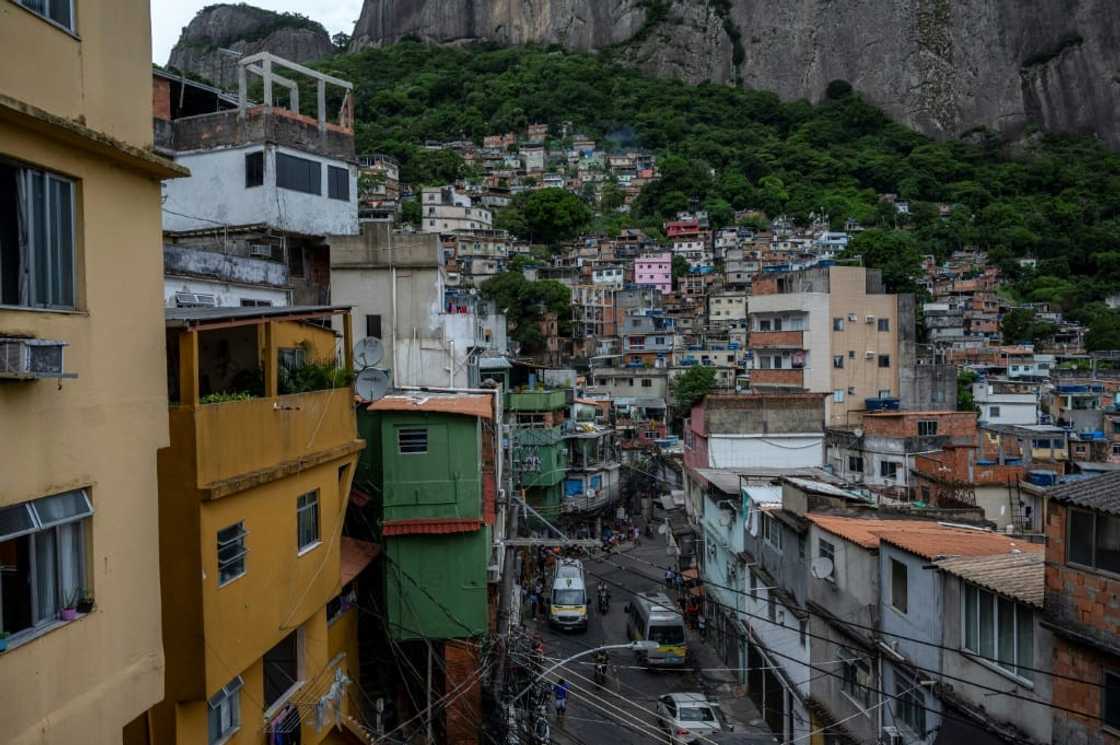

Costa, 45, lives in a small house accessed via a steep staircase near the top of Rocinha, a sprawling slum that spills down the hillside below in a jumble of narrow alleys and shacks.

Source: AFP

PAY ATTENTION: Follow us on Instagram - get the most important news directly in your favourite app!

The house has a small bedroom she shares with her teenage son. She has turned the rest of the space over to her kitchen, which is piled high with cooking equipment and ingredients donated by Gastromotiva, which started the program in 2020.

Relying on the online chef training she completed during the coronavirus pandemic and a knack for making a little go a long way, Costa prepares around 400 meals a week for the homeless, families who struggle to feed their children and anyone else who turns up hungry in her kitchen.

Who's 'crazy'?

That can be a big number in the favela, says the wiry dynamo, who cooks seven days a week with the help of a handful of volunteers, delivering her meals in biodegradable boxes thanks to an impromptu network of helpers.

"In a 100-meter radius, in any direction," there is always someone with an empty stomach, she says.

Source: AFP

Costa frowns at statistics showing that nearly 59 percent of Brazilians suffer from food insecurity. After all, the South American agricultural powerhouse is one of the world's top producers of soybeans, corn, beef and chicken.

"Where's the food?" she asks. "Why is it so expensive?"

She prides herself on using every last scrap of ingredients, turning carrot, beet and lime peelings into juices, for example.

She does not get paid for her work. To get by, she relies on the federal government's welfare programing which gives needy families 600 reais (around $120) a month.

Under a bridge bustling with vendors near the bottom of the favela, Anderson, a homeless man with a gash on his torso, gratefully accepts one of Costa's lunches.

"Ana has a heart too big for her chest," he beams.

Costa, who says she has seen her share of horror stories in the favela, calls cooking her "therapy."

"Some people say I'm crazy for donating all my time like this," she says.

"I think what's crazy is to sit there with your arms crossed instead of helping."

High cuisine in unlikely places

Source: AFP

Fellow volunteer chef Carlos Alberto da Silva says the program has helped save him from drug addiction, which he struggled with after his 20-year-old son was killed in a police operation several years ago -- a tragically common fate in the favelas.

Cooking "is what keeps me clean," says Da Silva, 52, who lives in the Chapeu Mangueira favela, on a hillside above the upscale Rio neighborhood of Leme.

Da Silva got up at 3:00 am to cook a dish of rice with saffron and black sesame seeds, served with roasted vegetables.

With the help of volunteers, he will distribute the delectable dish in Lapa, a central neighborhood with a large homeless population.

His kitchen is in a small restaurant he runs the rest of the week, installed above a community sports center in Chapeu Mangueira.

Source: AFP

He has struggled to attract clients in the favela.

But Da Silva, who dreams of studying at a top culinary institute, isn't giving up.

"I'll find funding, even if I have to go knock on every door," he says.

PAY ATTENTION: Сheck out news that is picked exactly for YOU ➡️ click on “Recommended for you” and enjoy!

Source: AFP