Mali mired in security problems two years after coup

Source: AFP

New feature: Check out news exactly for YOU ➡️ find “Recommended for you” block and enjoy!

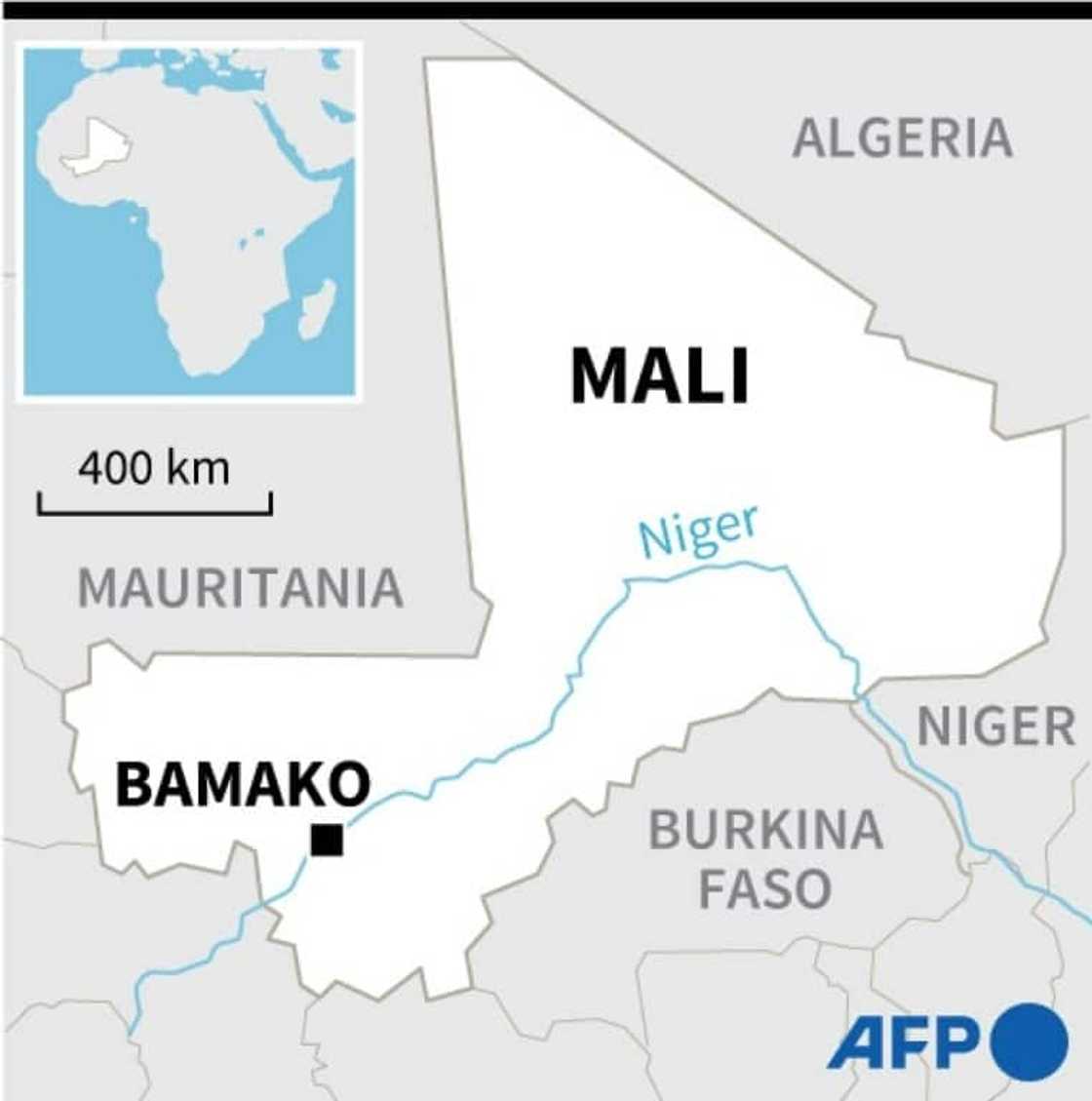

On August 18 2020, crowds in the Malian capital Bamako applauded as young colonels toppled a civilian government struggling to roll back a bloody jihadist insurgency.

Today, the looming anniversary of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita's ouster sees a country mired in problems.

On Monday, Mali's long-standing ally France packed its bags, withdrawing the last of its troops after falling out with the junta.

Here is a snapshot of what has happened since the coup:

Militarisation of politics

On taking power, the junta appointed military officers to key government jobs, installed a parliament, arrested political heavyweights under an anti-corruption probe and issued arrest warrants for those who had left the country.

Source: AFP

The takeover was completed when strongman Colonel Assimi Goita staged a de-facto second coup in May 2021, after which he was appointed interim president.

His junta's failure to hold promised elections on schedule prompted the 15-nation Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to impose sanctions, badly hitting one of the world's poorest economies.

The measures were lifted last month after ECOWAS accepted a timetable for restoring civilian rule by March 2024, although Mali remains suspended from its ranks.

Spreading insurgency

Keita had been facing street protests over failures to stem a jihadist campaign that erupted in northern Mali in 2012 and then spread to the centre of the country and neighbouring Niger and Burkina Faso.

Since then, jihadist attacks have continued and recently accelerated. More people were killed in the Sahel in the first six months of 2022 than the whole of 2021.

In Mali itself, attacks have occurred as far south as the outskirts of the capital Bamako, including the garrison town of Kati -- the launch pad of the 2018 coup.

A 2015 peace agreement between Bamako and armed ex-rebel groups in the north yielded little progress. The groups remain armed and firmly established.

In the rural bush, civilians are caught in the crossfire.

There is a new massacre almost every month. In August, 42 Malian soldiers were killed in Tessit, near the border with Niger and Burkina Faso, in one of the deadliest attacks on the army.

In June, more than 130 civilians were killed in Diallassagou, central Mali, in one night.

Shifting ties

The junta's message to the public is that of patriotism and national sovereignty.

With this strategy has come a dramatic shift in Mali's allegiances.

Source: AFP

The former colonial power France, which these days is accused of meddling and acting out of self-interest, has been sidelined.

In its stead, the junta has revived ties with the Kremlin that were first forged in the heady post-independence Socialist era.

This relationship once centred on education but now focusses heavily on defence.

Mali has received warplanes, combat helicopters and surveillance radars for its poorly equipped armed forces.

It is also being supported by Russian paramilitaries -- "mercenaries" from the Wagner group, say Western countries, while Mali insists they are military instructors.

A recent report by UN experts referred to the presence of "white soldiers" accompanying Malian soldiers at the scene of killings, including at Robinet El Ataye, where 33 civilians were killed in March.

In March, the army massacred about 300 people by summary execution in Moura in central Mali, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). Mali says its armed forces killed more than 2,000 jihadists.

New feature: check out news exactly for YOU ➡️ find "Recommended for you" block and enjoy!

Source: AFP